From Failure

“Great design, fabulous failures, and lessons learned.” That’s how a book called Design Disasters starts itself, and that’s exactly how my design career had been in my final year of education. I had some great ideas that only ever came out of fabulous failure. Deeper than that though, some of my visually great designs were conceptual failures, and some of my not-so-great designs have been backed by great concepts, theories, and desires.

I could refer to them as failures, but I like to think of them as more similar to scientific trials. A trial can be a full-time job. Entire careers are made on trials, both successful and failed, due to the mindset that they’re learning experiences. My own trials have provided a few different learning experiences that I took one or two key memories from and built my future process from them. The result of these trials has been growth, introspection on the causes of the failures, and better understanding of myself, from which I can take all of that learning to really nail down my design process and my artistic/design style.

One of my least successful trials was a failure on every front in the Fall of 2019. This client was the dance and arts instructor at WSU, and needed promotional material for her annual show “DanceScape.” This being the 30th show it was an important one. I had 29 years of successes to research, I had dancers and instructors to Q&A with, and I failed to connect the dots with any of it. During the proposal competition for the client, I defaulted to the generic, almost “cold” process that I’d been used to in the early days of the internship I had.

In my internship, we ran on a weekly schedule pounding out designs for promotional material. We’d get a snippet of the client’s work, and then design a postcard and poster off of those works. One of the proposals is selected, and then we move forward with that design to create a banner and a vinyl layout. One of those is selected, and we design a digital sign. The result of this process—especially in the early days when I was still trying to shed some light on my own process—was that I didn’t need to design something out of this world fantastic, and I didn’t always need the highest level of motivation to finish things. It would be laid out in a way that succeeds in being promotional material, and often times would be interesting to look at, but it wasn’t the highest level of design work. It was cold and dry.

That brings us back to the client proposal. Cold and dry is not a result that succeeds when you’re designing for a contemporary dance show. My initial proposals were a total failure. It was a failure of time management, so I was forced to just whip something up as quickly as possible to try and get something done. Obviously that wasn’t going to be good enough, and the client was gracious enough to give me a second chance. This time around, I managed my time much more successfully.

The “final” version was much better visually. Conceptually it lost that idea of identity, but the energy it gives off and the movement in the design is much more successful. Use of fifth channel clear ink (spot color magenta) adds a visual depth that looked really great on paper. Unfortunately for both of us, I still didn’t have the level of connection and understanding needed to create something truly successful. I ended up with a piece that just didn’t connect with the client. The energy, the warmth, the beauty of a dance show hadn’t come through. I had something interesting to look at, and that was all. It would’ve used fifth-channel clear ink to create a visually dynamic piece, I got a sense of movement and energy, but it wasn’t representative of the show that I was designing for.

In that reflection on my past, I recognized one major step in the growth in my abilities. In Winter 2018 we had a Winter Holiday Pop-Up Card sale, and then the following Valentine’s Day we had another pop-up/kinetic card sale. My design skills during the Winter sale weren’t quite up to snuff, and that was clear in the result. The concept I had come up with was actually really interesting. It told a cohesive story from product to product, from the stamp to the card to the posters advertising them. Unfortunately because my artistic skills weren’t there, I didn’t sell any cards. The design was amateur at best, and while the kinetic aspect was interesting it wasn’t complex or unique enough to succeed.

For Valentine’s Day, I suffered much the same issue. I hadn’t honed my design process yet, so I fell into the same amateurish design style that I’d used before. Then due to military commitments I wasn’t able to produce enough quality products to actually sell my cards. I took this in stride, buckled down, and decided to prove to myself that I could actually do something great. I had time, I had the resources, and I had the sales numbers to learn what worked and what didn’t. That’s when my “We Are Groot” card was conceived.

I took my baby Groot theme that I was using, and dove headfirst into the kinetic aspect of it. After half a dozen prototypes of kinetic elements, a dozen paper selections, and a number of visual adjustments, I started to line up what would come to be We Are Groot. I took the time to really create something great, instead of trying to just get something done for the sake of the grade. The paper selection gave the card a really nice canvas texture, and that texture tinted the printed colors in a way that turned out really nicely. It was sturdy, and the kinetic element was functional, complex, and interesting.

Contrast that to my winter sale’s “final product” of just using a cheap glossy printer paper, incredibly simple vector art, and a minimal kinetic element, and it was something that I’m truly proud of. Now if only I’d been able to get that figured out in an appropriate amount of time to put it up for sale… I still had much to learn. During the reflection with the client in Fall 2019, I recognized that I actually did know what to do, I just needed to acknowledge it and actually follow through with it during any given project in the time I’m given.

During this same time period in the Fall of 2019, a project that I initially thought was a total failure took place. Thankfully this was simply a passion project, so there was no external collateral damage in my lack of completion. I say “what I thought was failure” on purpose as initially I thought it was an absolute failure. Recently I realized that the growth that occurs in recognizing a lack of motivation towards a passion can be as important as pursuing a true passion. This is where my current mindset of “scientific trial” has come into being. In the initial proposals of my passion project that semester—which you can read here—I was floundering. I went from project to project to project just trying to figure out what I wanted to do. I knew I wanted to do something with cars. I love cars, and pursuing some sort of car design was something that I wanted to move forward with.

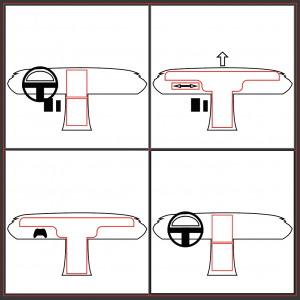

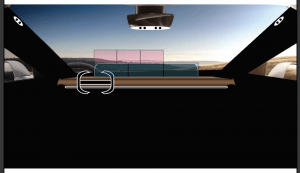

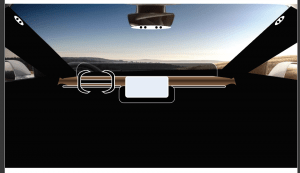

My first failure was in not being specific enough in my initial proposal. I left it so vague that despite having a two page proposal, I still had too many options to really do anything. It took months to really figure out what I wanted to do. Finally, I had trimmed my proposal down enough to know that I wanted to create the infotainment display of a car, and then do some light animation to exemplify the way it would move. Unfortunately by that point, following through with this passion project had lost my passion. It sat dead for so long that my drive died too. I had 9 months of work that resulted in some scraps. It was nothing, so I thought. What I actually had? I had 9 months of experience and practice to reflect on and perform better in the future. Which I did.

The culmination of these trials exists in two major projects. My website and my capstone exhibition piece. My website, https://hinterdesign.com, was a passion project that I took to heart. I worked on this site hours a day, days on end, for close to 6 weeks. I wanted to do something I hadn’t done before, so I taught myself to develop locally hosted WordPress content, using a customizable page builder that I had never used before. It was new, it was popular, and it was relevant, and I was in. It turned out better than I’d ever thought it would. By the nature of the project, it’s an always going to be an on-going project, but I had the initial framework laid down in a short amount of time. I was playing, prototyping, and producing faster than I’d done before. I’m still always making improvements, but it was a clear example of my prototype-to-production process becoming more efficient and more effective.

My capstone piece was the best example of my growth, though. From January to March, my group and I had been conceptualizing the exhibit, our pieces, the story we wanted to tell. We had decided on the idea of “Sublime,” the sort of magical feeling you get in an experience that is distinctly human. By March, we had some rough drafts of personal concepts, a solid concept, and a few prototypes of our projects. Then the lockdowns hit.

After almost three weeks of worrying as the school figured out how to move forward, it was time to get back to work. We had to change the entire show except for our base concept. Our prototypes were reset, our personal concepts were reworked, and the exhibit plans were scrapped. It was then turned into the show you see here at the Design Program website.

Over the first two weeks after online meetings started, I was able to nail down a concept and two rough drafts. Two weeks after that, I had a final piece and the others conceptualizing, and a week later they were on the page nearing the opening of the exhibit. I was able to write out my concept thoroughly enough to know what to do, without being so specific I can’t expand anything. I was able to teach myself techniques that I wanted to learn, without becoming so overwhelmed that I had to cut corners. With a project that’s supposed to take almost 6 months to finish, I got it done in less than 2. At the end of it, I realized that it was because I’d finally internalized everything that I’d been learning in regards to not just any design process, but my design process. That’s something that I can take with me in any project over any medium.

These trials, these failures, were what truly taught me through my career. Yes, I was picking up a lot of software and technology skills throughout my academic career, but I’ve always enjoyed new software and have been good at picking things up quickly.

The times that I learned to think for myself, fend for myself, and truly make something of myself were after instances of failure, and then me forcing myself to not fall into the same hole twice. There may be similar instances in my past and future, but now I know the signs, and am able to course-correct to succeed.